Are There Animals That Can Incestually Breed With No Issues

Mutual fruit fly females adopt to mate with their own brothers over unrelated males.[1]

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or convenance of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically.[ii] By illustration, the term is used in man reproduction, but more than commonly refers to the genetic disorders and other consequences that may arise from expression of deleterious or recessive traits resulting from incestuous sexual relationships and consanguinity.

Inbreeding results in homozygosity, which can increase the chances of offspring being affected by deleterious or recessive traits.[three] This usually leads to at least temporarily decreased biological fitness of a population[four] [five] (called inbreeding depression), which is its ability to survive and reproduce. An individual who inherits such deleterious traits is colloquially referred to equally inbred. The abstention of expression of such deleterious recessive alleles caused past inbreeding, via inbreeding avoidance mechanisms, is the main selective reason for outcrossing.[6] [7] Crossbreeding between populations also often has positive furnishings on fettle-related traits,[viii] simply also sometimes leads to negative effects known as outbreeding depression. However, increased homozygosity increases probability of fixing benign alleles and too slightly decreases probability of fixing deleterious alleles in population.[9] Inbreeding can result in purging of deleterious alleles from a population through purifying selection.[10] [11] [12]

Inbreeding is a technique used in selective convenance. For example, in livestock breeding, breeders may use inbreeding when trying to constitute a new and desirable trait in the stock and for producing distinct families within a breed, but will demand to spotter for undesirable characteristics in offspring, which tin then be eliminated through further selective breeding or alternative. Inbreeding also helps to ascertain the type of gene action affecting a trait. Inbreeding is likewise used to reveal deleterious recessive alleles, which tin can so be eliminated through assortative breeding or through alternative. In found breeding, inbred lines are used as stocks for the creation of hybrid lines to make use of the effects of heterosis. Inbreeding in plants likewise occurs naturally in the grade of self-pollination.

Inbreeding can significantly influence gene expression which tin can prevent inbreeding low.[thirteen]

Overview [edit]

Offspring of biologically related persons are discipline to the possible effects of inbreeding, such equally congenital nascency defects. The chances of such disorders are increased when the biological parents are more than closely related. This is because such pairings have a 25% probability of producing homozygous zygotes, resulting in offspring with two recessive alleles, which tin can produce disorders when these alleles are deleterious.[xiv] Because most recessive alleles are rare in populations, it is unlikely that two unrelated marriage partners will both exist carriers of the same deleterious allele; however, because close relatives share a large fraction of their alleles, the probability that any such deleterious allele is inherited from the common ancestor through both parents is increased dramatically. For each homozygous recessive individual formed in that location is an equal chance of producing a homozygous ascendant individual — one completely devoid of the harmful allele. Contrary to common belief, inbreeding does non in itself alter allele frequencies, but rather increases the relative proportion of homozygotes to heterozygotes; nevertheless, considering the increased proportion of deleterious homozygotes exposes the allele to natural choice, in the long run its frequency decreases more rapidly in inbred populations. In the short term, incestuous reproduction is expected to increase the number of spontaneous abortions of zygotes, perinatal deaths, and postnatal offspring with nascence defects.[fifteen] The advantages of inbreeding may exist the result of a trend to preserve the structures of alleles interacting at different loci that take been adapted together past a common selective history.[xvi]

Malformations or harmful traits can stay within a population due to a high homozygosity rate, and this will crusade a population to become fixed for certain traits, like having likewise many bones in an area, like the vertebral column of wolves on Island Royale or having cranial abnormalities, such as in Northern elephant seals, where their cranial bone length in the lower mandibular tooth row has changed. Having a loftier homozygosity rate is problematic for a population considering information technology will unmask recessive deleterious alleles generated by mutations, reduce heterozygote advantage, and it is detrimental to the survival of small-scale, endangered animal populations.[17] When deleterious recessive alleles are unmasked due to the increased homozygosity generated past inbreeding, this can cause inbreeding depression.[xviii]

There may also be other deleterious furnishings too those caused by recessive diseases. Thus, similar immune systems may be more than vulnerable to infectious diseases (run across Major histocompatibility complex and sexual choice).[19]

Inbreeding history of the population should as well exist considered when discussing the variation in the severity of inbreeding depression between and within species. With persistent inbreeding, in that location is bear witness that shows that inbreeding depression becomes less severe. This is associated with the unmasking and elimination of severely deleterious recessive alleles. However, inbreeding depression is non a temporary phenomenon considering this elimination of deleterious recessive alleles will never be consummate. Eliminating slightly deleterious mutations through inbreeding under moderate pick is not as constructive. Fixation of alleles most likely occurs through Muller'south ratchet, when an asexual population's genome accumulates deleterious mutations that are irreversible.[20]

Despite all its disadvantages, inbreeding tin can also have a diverseness of advantages, such as ensuring a child produced from the mating contains, and volition laissez passer on, a higher percentage of its mother/father's genetics, reducing the recombination load,[21] and allowing the expression of recessive advantageous phenotypes. Some species with a Haplodiploidy mating organisation depend on the ability to produce sons to mate with as a ways of ensuring a mate tin be establish if no other male is available. It has been proposed that under circumstances when the advantages of inbreeding outweigh the disadvantages, preferential convenance within small groups could exist promoted, potentially leading to speciation.[22]

Genetic disorders [edit]

Animation of uniparental isodisomy

Autosomal recessive disorders occur in individuals who take two copies of an allele for a particular recessive genetic mutation.[23] Except in certain rare circumstances, such as new mutations or uniparental disomy, both parents of an individual with such a disorder will be carriers of the factor. These carriers practice not brandish whatsoever signs of the mutation and may exist unaware that they conduct the mutated factor. Since relatives share a higher proportion of their genes than do unrelated people, information technology is more probable that related parents will both be carriers of the same recessive allele, and therefore their children are at a higher chance of inheriting an autosomal recessive genetic disorder. The extent to which the risk increases depends on the degree of genetic relationship betwixt the parents; the risk is greater when the parents are close relatives and lower for relationships between more distant relatives, such as 2nd cousins, though still greater than for the general population.[24]

Children of parent-child or sibling-sibling unions are at an increased take a chance compared to cousin-cousin unions.[25] : 3 Inbreeding may event in a greater than expected phenotypic expression of deleterious recessive alleles within a population.[26] Equally a result, offset-generation inbred individuals are more likely to show physical and wellness defects,[27] [28] including:

- Reduced fertility both in litter size and sperm viability

- Increased genetic disorders

- Fluctuating facial disproportion

- Lower nascency rate

- Higher infant mortality and child mortality[29]

- Smaller adult size

- Loss of allowed system role

- Increased cardiovascular risks[thirty]

The isolation of a small population for a flow of time tin lead to inbreeding inside that population, resulting in increased genetic relatedness between breeding individuals. Inbreeding low can besides occur in a large population if individuals tend to mate with their relatives, instead of mating randomly.

Due to college prenatal and postnatal mortality rates, some individuals in the first generation of inbreeding will not live on to reproduce.[31] Over time, with isolation, such as a population bottleneck caused by purposeful (assortative) convenance or natural environmental factors, the deleterious inherited traits are culled.[half dozen] [7] [32]

Island species are oft very inbred, as their isolation from the larger grouping on a mainland allows natural selection to piece of work on their population. This type of isolation may issue in the formation of race or even speciation, as the inbreeding start removes many deleterious genes, and permits the expression of genes that let a population to conform to an ecosystem. As the adaptation becomes more than pronounced, the new species or race radiates from its entrance into the new space, or dies out if it cannot accommodate and, most importantly, reproduce.[33]

The reduced genetic variety, for example due to a bottleneck will unavoidably increase inbreeding for the unabridged population. This may mean that a species may not exist able to adapt to changes in environmental atmospheric condition. Each individual will have similar immune systems, equally immune systems are genetically based. When a species becomes endangered, the population may fall below a minimum whereby the forced interbreeding between the remaining animals will result in extinction.

Natural breedings include inbreeding by necessity, and well-nigh animals only drift when necessary. In many cases, the closest bachelor mate is a mother, sister, grandmother, father, blood brother, or granddad. In all cases, the environment presents stresses to remove from the population those individuals who cannot survive because of illness.[ citation needed ]

There was an assumption[ by whom? ] that wild populations practice not inbreed; this is non what is observed in some cases in the wild. However, in species such as horses, animals in wild or feral weather condition often drive off the young of both sexes, idea to exist a mechanism by which the species instinctively avoids some of the genetic consequences of inbreeding.[34] In full general, many mammal species, including humanity's closest primate relatives, avoid close inbreeding possibly due to the deleterious effects.[25] : 6

Examples [edit]

Although there are several examples of inbred populations of wild animals, the negative consequences of this inbreeding are poorly documented.[ commendation needed ] In the Southward American sea panthera leo, at that place was concern that recent population crashes would reduce genetic diverseness. Historical analysis indicated that a population expansion from simply ii matrilineal lines was responsible for most of the individuals inside the population. Nevertheless, the diversity within the lines allowed great variation in the gene pool that may assistance to protect the South American sea lion from extinction.[35]

In lions, prides are oft followed past related males in bachelor groups. When the dominant male is killed or driven off by one of these bachelors, a father may be replaced past his son. There is no mechanism for preventing inbreeding or to ensure outcrossing. In the prides, almost lionesses are related to one some other. If at that place is more than i ascendant male, the group of alpha males are usually related. Two lines are so being "line bred". As well, in some populations, such as the Crater lions, it is known that a population clogging has occurred. Researchers found far greater genetic heterozygosity than expected.[36] In fact, predators are known for low genetic variance, forth with most of the acme portion of the trophic levels of an ecosystem.[37] Additionally, the blastoff males of two neighboring prides tin can be from the same litter; one blood brother may come to learn leadership over another's pride, and subsequently mate with his 'nieces' or cousins. However, killing another male's cubs, upon the takeover, allows the new selected gene complement of the incoming alpha male to prevail over the previous male person. There are genetic assays being scheduled for lions to determine their genetic diversity. The preliminary studies show results inconsistent with the outcrossing prototype based on private environments of the studied groups.[36]

In Central California, body of water otters were thought to have been driven to extinction due to over hunting, until a small colony was discovered in the Point Sur region in the 1930s.[38] Since so, the population has grown and spread along the central Californian coast to around ii,000 individuals, a level that has remained stable for over a decade. Population growth is limited by the fact that all Californian sea otters are descended from the isolated colony, resulting in inbreeding.[39]

Cheetahs are some other example of inbreeding. Thousands of years ago, the cheetah went through a population bottleneck that reduced its population dramatically so the animals that are alive today are all related to one another. A issue from inbreeding for this species has been high juvenile mortality, low fecundity, and poor breeding success.[40]

In a written report on an island population of song sparrows, individuals that were inbred showed significantly lower survival rates than outbred individuals during a severe wintertime weather condition related population crash. These studies show that inbreeding depression and ecological factors have an influence on survival.[20]

Measures [edit]

A measure of inbreeding of an individual A is the probability F(A) that both alleles in one locus are derived from the same allele in an ancestor. These 2 identical alleles that are both derived from a common ancestor are said to be identical by descent. This probability F(A) is called the "coefficient of inbreeding".[41]

Another useful measure that describes the extent to which two individuals are related (say individuals A and B) is their coancestry coefficient f(A,B), which gives the probability that one randomly selected allele from A and another randomly selected allele from B are identical by descent.[42] This is also denoted equally the kinship coefficient between A and B.[43]

A item case is the self-coancestry of individual A with itself, f(A,A), which is the probability that taking one random allele from A and and then, independently and with replacement, another random allele also from A, both are identical past descent. Since they tin can be identical by descent past sampling the same allele or by sampling both alleles that happen to exist identical by descent, we have f(A,A) = ane/2 + F(A)/ii.[44]

Both the inbreeding and the coancestry coefficients can be defined for specific individuals or as average population values. They tin can be computed from genealogies or estimated from the population size and its breeding properties, simply all methods assume no selection and are express to neutral alleles.

There are several methods to compute this percent. The 2 master ways are the path method[45] [41] and the tabular method.[46] [47]

Typical coancestries betwixt relatives are as follows:

- Father/daughter or mother/son → 25% ( 1⁄4 )

- Brother/sister → 25% ( one⁄4 )

- Grandfather/granddaughter or grandmother/grandson → 12.five% ( 1⁄viii )

- Half-blood brother/half-sister, Double cousins → 12.5% ( 1⁄8 )

- Uncle/niece or aunt/nephew → 12.v% ( i⁄8 )

- Smashing-grandfather/neat-granddaughter or great-grandmother/keen-grandson → six.25% ( 1⁄16 )

- One-half-uncle/niece or one-half-aunt/nephew → 6.25% ( ane⁄16 )

- First cousins → 6.25% ( one⁄sixteen )

Animals [edit]

Wild animals [edit]

- Banded mongoose females regularly mate with their fathers and brothers.[48]

- Bed bugs: Northward Carolina State University found that bedbugs, in contrast to most other insects, tolerate incest and are able to genetically withstand the furnishings of inbreeding quite well.[49]

- Common fruit fly females prefer to mate with their own brothers over unrelated males.[one]

- Cottony cushion scales: 'It turns out that females in these hermaphrodite insects are not really fertilizing their eggs themselves, just instead are having this done by a parasitic tissue that infects them at nascency,' says Laura Ross of Oxford Academy's Department of Zoology. 'Information technology seems that this infectious tissue derives from left-over sperm from their father, who has constitute a sneaky mode of having more than children by mating with his daughters.'[l]

- Adactylidium: The single male offspring mite mates with all the daughters when they are yet in the mother. The females, now impregnated, cut holes in their mother's body so that they can emerge to find new thrips eggs. The male emerges besides, just does not expect for nutrient or new mates, and dies after a few hours. The females dice at the age of four days, when their ain offspring swallow them alive from the inside.[51]

Domestic animals [edit]

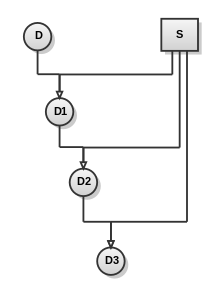

An intensive form of inbreeding where an private S is mated to his girl D1, granddaughter D2 and then on, in social club to maximise the percentage of South'due south genes in the offspring. 87.five% of D3's genes would come from S, while D4 would receive 93.75% of their genes from Southward.[54]

Breeding in domestic animals is primarily assortative convenance (see selective breeding). Without the sorting of individuals by trait, a breed could not be established, nor could poor genetic cloth exist removed. Homozygosity is the instance where similar or identical alleles combine to limited a trait that is not otherwise expressed (recessiveness). Inbreeding exposes recessive alleles through increasing homozygosity.[55]

Breeders must avoid breeding from individuals that demonstrate either homozygosity or heterozygosity for disease causing alleles.[56] The goal of preventing the transfer of deleterious alleles may exist achieved by reproductive isolation, sterilization, or, in the extreme instance, culling. Alternative is non strictly necessary if genetics are the only issue in mitt. Small animals such as cats and dogs may be sterilized, but in the case of large agricultural animals, such equally cattle, culling is usually the only economic option.

The result of coincidental breeders who inbreed irresponsibly is discussed in the following quotation on cattle:

Meanwhile, milk production per cow per lactation increased from 17,444 lbs to 25,013 lbs from 1978 to 1998 for the Holstein breed. Hateful breeding values for milk of Holstein cows increased past 4,829 lbs during this period.[57] High producing cows are increasingly difficult to brood and are discipline to college wellness costs than cows of lower genetic merit for production (Cassell, 2001).

Intensive selection for college yield has increased relationships among animals within breed and increased the rate of casual inbreeding.

Many of the traits that impact profitability in crosses of mod dairy breeds have not been studied in designed experiments. Indeed, all crossbreeding research involving N American breeds and strains is very dated (McAllister, 2001) if it exists at all.[58]

The BBC produced two documentaries on domestic dog inbreeding titled Pedigree Dogs Exposed and Pedigree Dogs Exposed: Three Years On that certificate the negative health consequences of excessive inbreeding.

Linebreeding [edit]

Linebreeding is a form of inbreeding. There is no clear distinction between the 2 terms, only linebreeding may encompass crosses betwixt individuals and their descendants or 2 cousins.[54] [59] This method can be used to increment a detail animal's contribution to the population.[54] While linebreeding is less likely to crusade problems in the first generation than does inbreeding, over time, linebreeding tin reduce the genetic diversity of a population and cause problems related to a too-small genetic pool that may include an increased prevalence of genetic disorders and inbreeding low.[ citation needed ]

Outcrossing [edit]

Outcrossing is where two unrelated individuals are crossed to produce progeny. In outcrossing, unless in that location is verifiable genetic information, one may find that all individuals are distantly related to an ancient progenitor. If the trait carries throughout a population, all individuals can have this trait. This is called the founder consequence. In the well established breeds, that are normally bred, a large genetic pool is present. For example, in 2004, over 18,000 Persian cats were registered.[60] A possibility exists for a complete outcross, if no barriers be between the individuals to breed. However, it is non always the case, and a form of afar linebreeding occurs. Once again it is up to the assortative breeder to know what sort of traits, both positive and negative, exist within the diversity of one breeding. This diversity of genetic expression, inside fifty-fifty close relatives, increases the variability and diversity of viable stock.

Laboratory animals [edit]

Systematic inbreeding and maintenance of inbred strains of laboratory mice and rats is of slap-up importance for biomedical enquiry. The inbreeding guarantees a consequent and uniform brute model for experimental purposes and enables genetic studies in congenic and knock-out animals. In order to achieve a mouse strain that is considered inbred, a minimum of 20 sequential generations of sibling matings must occur. With each successive generation of breeding, homozygosity in the entire genome increases, eliminating heterozygous loci. With 20 generations of sibling matings, homozygosity is occurring at roughly 98.seven% of all loci in the genome, assuasive for these offspring to serve as animal models for genetic studies.[61] The utilise of inbred strains is too of import for genetic studies in animal models, for example to distinguish genetic from environmental effects. The mice that are inbred typically show considerably lower survival rates.

Humans [edit]

Effects [edit]

Inbreeding increases homozygosity, which can increment the chances of the expression of deleterious recessive alleles and therefore has the potential to decrease the fitness of the offspring. With continuous inbreeding, genetic variation is lost and homozygosity is increased, enabling the expression of recessive deleterious alleles in homozygotes. The coefficient of inbreeding, or the degree of inbreeding in an individual, is an gauge of the pct of homozygous alleles in the overall genome.[63] The more than biologically related the parents are, the greater the coefficient of inbreeding, since their genomes have many similarities already. This overall homozygosity becomes an issue when at that place are deleterious recessive alleles in the factor pool of the family.[64] By pairing chromosomes of like genomes, the chance for these recessive alleles to pair and become homozygous greatly increases, leading to offspring with autosomal recessive disorders.[64]

Inbreeding is specially problematic in pocket-size populations where the genetic variation is already limited.[65] By inbreeding, individuals are further decreasing genetic variation by increasing homozygosity in the genomes of their offspring.[66] Thus, the likelihood of deleterious recessive alleles to pair is significantly higher in a small inbreeding population than in a larger inbreeding population.[65]

The fitness consequences of consanguineous mating have been studied since their scientific recognition past Charles Darwin in 1839.[67] [68] Some of the well-nigh harmful effects known from such convenance includes its effects on the bloodshed charge per unit too every bit on the general wellness of the offspring.[69] Since the 1960s, in that location have been many studies to support such debilitating effects on the homo organism.[66] [67] [69] [lxx] [71] Specifically, inbreeding has been found to decrease fertility as a direct result of increasing homozygosity of deleterious recessive alleles.[71] [72] Fetuses produced by inbreeding also face a greater risk of spontaneous abortions due to inherent complications in evolution.[73] Among mothers who feel stillbirths and early infant deaths, those that are inbreeding have a significantly higher risk of reaching repeated results with future offspring.[74] Additionally, consanguineous parents possess a high run a risk of premature nativity and producing underweight and undersized infants.[75] Viable inbred offspring are also probable to be inflicted with physical deformities and genetically inherited diseases.[63] Studies accept confirmed an increase in several genetic disorders due to inbreeding such as blindness, hearing loss, neonatal diabetes, limb malformations, disorders of sex development, schizophrenia and several others.[63] [76] Moreover, in that location is an increased take chances for congenital heart disease depending on the inbreeding coefficient (Encounter coefficient of inbreeding) of the offspring, with significant take chances accompanied past an F =.125 or higher.[27]

Prevalence [edit]

The general negative outlook and eschewal of inbreeding that is prevalent in the Western earth today has roots from over 2000 years ago. Specifically, written documents such as the Bible illustrate that there take been laws and social community that accept chosen for the abstention from inbreeding. Along with cultural taboos, parental instruction and awareness of inbreeding consequences have played large roles in minimizing inbreeding frequencies in areas like Europe. That existence so, in that location are less urbanized and less populated regions across the earth that have shown continuity in the do of inbreeding.

The continuity of inbreeding is ofttimes either past option or unavoidably due to the limitations of the geographical area. When past choice, the rate of consanguinity is highly dependent on faith and culture.[65] In the Western earth some Anabaptist groups are highly inbred because they originate from small founder populations and until[ clarification needed ] today[ when? ] marriage outside the groups is not allowed for members.[ citation needed ] Especially the Reidenbach Old Order Mennonites[77] and the Hutterites stem from very small founder populations. The same is truthful for some Hasidic and Haredi Jewish groups.

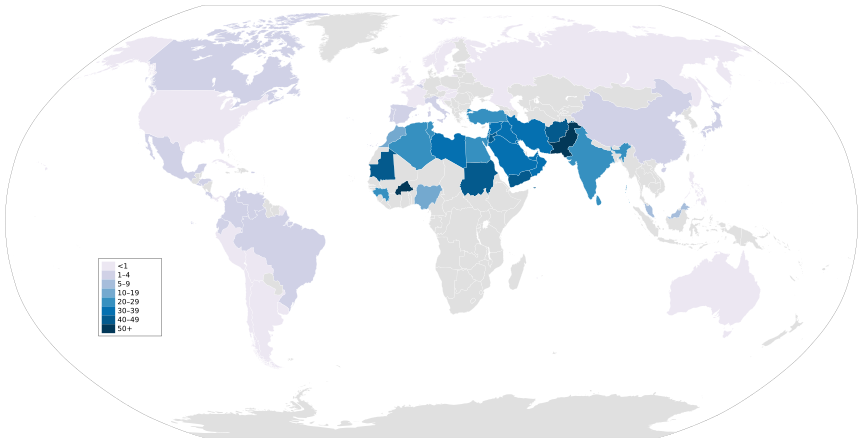

Of the practicing regions, Middle Eastern and northern Africa territories testify the greatest frequencies of consanguinity. [65]

Amongst these populations with loftier levels of inbreeding, researchers have institute several disorders prevalent among inbred offspring. In Lebanon, Kingdom of saudi arabia, Arab republic of egypt, and in Israel, the offspring of consanguineous relationships accept an increased take a chance of congenital malformations, built heart defects, congenital hydrocephalus and neural tube defects.[65] Furthermore, amidst inbred children in Palestine and Lebanese republic, at that place is a positive clan between consanguinity and reported crack lip/palate cases.[65] Historically, populations of Qatar have engaged in consanguineous relationships of all kinds, leading to loftier adventure of inheriting genetic diseases. Every bit of 2014, around 5% of the Qatari population suffered from hereditary hearing loss; most were descendants of a consanguineous relationship.[78]

Royalty and nobility [edit]

Inter-dignity marriage was used every bit a method of forming political alliances amongst elites. These ties were ofttimes sealed merely upon the birth of progeny within the bundled spousal relationship. Thus wedlock was seen as a union of lines of dignity and not as a contract between individuals.

Royal intermarriage was often proficient amid European regal families, normally for interests of state. Over time, due to the relatively limited number of potential consorts, the gene pool of many ruling families grew progressively smaller, until all European royalty was related. This also resulted in many being descended from a sure person through many lines of descent, such as the numerous European royalty and nobility descended from the British Queen Victoria or King Christian 9 of Denmark.[79] The House of Habsburg was known for its intermarriages; the Habsburg lip often cited as an ill-result. The closely related houses of Habsburg, Bourbon, Braganza and Wittelsbach besides frequently engaged in first-cousin unions also as the occasional double-cousin and uncle–niece marriages.

In aboriginal Egypt, royal women were believed to comport the bloodlines then it was advantageous for a pharaoh to marry his sister or half-sister;[80] in such cases a special combination between endogamy and polygamy is found. Commonly, the sometime ruler'southward eldest son and daughter (who could be either siblings or half-siblings) became the new rulers. All rulers of the Ptolemaic dynasty uninterruptedly from Ptolemy IV (Ptolemy 2 married his sis but had no upshot) were married to their brothers and sisters, so every bit to keep the Ptolemaic blood "pure" and to strengthen the line of succession. King Tutankhamun'southward female parent is reported to have been the half-sister to his begetter,[81] Cleopatra VII (too called Cleopatra Half dozen) and Ptolemy 13, who married and became co-rulers of ancient Egypt following their father's expiry, are the most widely known example.[82]

See also [edit]

- Alvarez example

- Coefficient of relationship

- Consanguinity

- Cousin marriage

- Cousin marriage in the Centre East

- Evolution of sexual reproduction

- Exogamy

- Founder effect

- F-statistics

- Fritzl case

- Genetic variety

- Genetic purging

- Genetic sexual attraction

- Heterozygote advantage

- Identical ancestors point

- Inbreeding depression

- Inbreeding in fish

- Incest

- Incest taboo

- Insular dwarfism

- Intellectual inbreeding

- Legality of incest

- List of coupled cousins

- Mahram

- Outbreeding depression

- Outcrossing

- Proximity of blood

- Prohibited degree of kinship

- Selective convenance

- Self-incompatibility in plants (how some plants avoid inbreeding)

References [edit]

- ^ a b Loyau A, Cornuau JH, Clobert J, Danchin Eastward (2012). "Incestuous sisters: mate preference for brothers over unrelated males in Drosophila melanogaster". PLOS Ane. 7 (12): e51293. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...751293L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051293. PMC3519633. PMID 23251487.

- ^ Inbreeding at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Nabulsi MM, Tamim H, Sabbagh M, Obeid MY, Yunis KA, Bitar FF (February 2003). "Parental consanguinity and built heart malformations in a developing country". American Periodical of Medical Genetics. Function A. 116A (four): 342–7. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.10020. PMID 12522788. S2CID 44576506.

- ^ Jiménez JA, Hughes KA, Alaks G, Graham L, Lacy RC (October 1994). "An experimental written report of inbreeding depression in a natural habitat". Science. 266 (5183): 271–3. Bibcode:1994Sci...266..271J. doi:ten.1126/science.7939661. PMID 7939661.

- ^ Chen Ten (1993). "Comparison of inbreeding and outbreeding in hermaphroditic Arianta arbustorum (50.) (land snail)". Heredity. 71 (five): 456–461. doi:10.1038/hdy.1993.163.

- ^ a b Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE (September 1985). "Genetic damage, mutation, and the evolution of sex". Science. 229 (4719): 1277–81. Bibcode:1985Sci...229.1277B. doi:10.1126/science.3898363. PMID 3898363.

- ^ a b Michod RE. Eros and Evolution: A Natural Philosophy of Sex. (1994) Perseus Books, ISBN 0-201-40754-X

- ^ Lynch M (1991). "The Genetic Interpretation of Inbreeding Depression and Outbreeding Depression". Development; International Journal of Organic Evolution. Oregon: Gild for the Written report of Evolution. 45 (3): 622–629. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb04333.ten. PMID 28568822. S2CID 881556. [ page needed ]

- ^ Whitlock MC (June 2003). "Fixation probability and fourth dimension in subdivided populations". Genetics. 164 (2): 767–79. doi:10.1093/genetics/164.2.767. PMC1462574. PMID 12807795.

- ^ Tien NS, Sabelis MW, Egas Thousand (March 2015). "Inbreeding depression and purging in a haplodiploid: gender-related furnishings". Heredity. 114 (3): 327–32. doi:10.1038/hdy.2014.106. PMC4815584. PMID 25407077.

- ^ Peer Thousand, Taborsky G (February 2005). "Outbreeding depression, but no inbreeding depression in haplodiploid Ambrosia beetles with regular sibling mating". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 59 (2): 317–23. doi:ten.1554/04-128. PMID 15807418. S2CID 198156378.

- ^ Gulisija D, Crow JF (May 2007). "Inferring purging from pedigree information". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 61 (v): 1043–51. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00088.x. PMID 17492959. S2CID 24302475.

- ^ García C, Avila V, Quesada H, Caballero A (2012). "Factor-Expression Changes Acquired by Inbreeding Protect Confronting Inbreeding Depression in Drosophila". Genetics. 192 (one): 161–72. doi:10.1534/genetics.112.142687. PMC3430533. PMID 22714404.

- ^ Livingstone FB (1969). "Genetics, Ecology, and the Origins of Incest and Exogamy". Current Anthropology. 10: 45–62. doi:10.1086/201009. S2CID 84009643.

- ^ Thornhill NW (1993). The Natural History of Inbreeding and Outbreeding: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing. ISBN978-0-226-79854-7.

- ^ Shields, W. Thou. 1982. Philopatry, Inbreeding, and the Evolution of Sex. Print. 50–69.

- ^ Meagher S, Penn DJ, Potts WK (March 2000). "Male-male competition magnifies inbreeding depression in wild house mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the Usa of America. 97 (7): 3324–9. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.3324M. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.7.3324. PMC16238. PMID 10716731.

- ^ Swindell WR, et al. (2006). "Selection and Inbreeding Low: Furnishings of Inbreeding Rate and Inbreeding Environment". Evolution. 60 (v): 1014–1022. doi:10.1554/05-493.1. PMID 16817541. S2CID 198156086.

- ^ Lieberman D, Tooby J, Cosmides L (April 2003). "Does morality take a biological basis? An empirical test of the factors governing moral sentiments relating to incest". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 270 (1517): 819–26. doi:ten.1098/rspb.2002.2290. PMC1691313. PMID 12737660.

- ^ a b Pusey A, Wolf Chiliad (May 1996). "Inbreeding avoidance in animals". Trends in Ecology & Development. 11 (v): 201–half-dozen. doi:x.1016/0169-5347(96)10028-8. PMID 21237809.

- ^ Shields WM (1982). Philopatry, inbreeding, and the evolution of sexual practice. Albany: State University of New York Printing. ISBN978-0-87395-618-5.

- ^ Joly Eastward (December 2011). "The existence of species rests on a metastable equilibrium between inbreeding and outbreeding. An essay on the close human relationship between speciation, inbreeding and recessive mutations". Biology Direct. six: 62. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-62. PMC3275546. PMID 22152499.

- ^ Hartl, D.L., Jones, Eastward.W. (2000) Genetics: Analysis of Genes and Genomes. Fifth Edition. Jones and Bartlett Publishers Inc., pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-7637-1511-5.

- ^ Kingston HM (April 1989). "ABC of clinical genetics. Genetics of common disorders". BMJ. 298 (6678): 949–52. doi:10.1136/bmj.298.6678.949. PMC1836181. PMID 2497870.

- ^ a b Wolf AP, Durham WH, eds. (2005). Inbreeding, incest, and the incest taboo: the land of noesis at the turn. Stanford University Press. ISBN978-0-8047-5141-4.

- ^ Griffiths AJ, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, Lewontin RC, Gelbart WM (1999). An introduction to genetic assay. New York: W. H. Freeman. pp. 726–727. ISBN978-0-7167-3771-ane.

- ^ a b Bittles AH, Black ML (January 2010). "Evolution in wellness and medicine Sackler colloquium: Consanguinity, man evolution, and complex diseases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United states of America. 107 Suppl 1 (suppl 1): 1779–86. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.1779B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906079106. PMC2868287. PMID 19805052.

- ^ Fareed M, Afzal M (2014). "Prove of inbreeding depression on summit, weight, and body mass index: a population-based child accomplice written report". American Journal of Human Biology. 26 (6): 784–95. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22599. PMID 25130378. S2CID 6086127.

- ^ Fareed Thousand, Kaisar Ahmad K, Azeem Anwar Chiliad, Afzal M (January 2017). "Impact of consanguineous marriages and degrees of inbreeding on fertility, child mortality, secondary sexual activity ratio, selection intensity, and genetic load: a cantankerous-sectional study from Northern India". Pediatric Research. 81 (one): 18–26. doi:10.1038/pr.2016.177. PMID 27632780.

- ^ Fareed M, Afzal M (April 2016). "Increased cardiovascular risks associated with familial inbreeding: a population-based report of boyish cohort". Register of Epidemiology. 26 (4): 283–92. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.03.001. PMID 27084548.

- ^ Bittles AH, Grant JC, Shami SA (June 1993). "Consanguinity every bit a determinant of reproductive behaviour and mortality in Pakistan". International Journal of Epidemiology (Submitted manuscript). 22 (three): 463–7. doi:10.1093/ije/22.3.463. PMID 8359962.

- ^ Kirkpatrick M, Jarne P (February 2000). "The Effects of a Bottleneck on Inbreeding Depression and the Genetic Load". The American Naturalist. 155 (2): 154–167. doi:10.1086/303312. PMID 10686158. S2CID 4375158.

- ^ Leck CF (1980). "Establishment of New Population Centers with Changes in Migration Patterns" (PDF). Periodical of Field Ornithology. 51 (2): 168–173. JSTOR 4512538.

- ^ "ADVS 3910 Wild Horses Behavior", Higher of Agriculture, Utah State University.

- ^ Freilich Due south, Hoelzel AR, Choudhury SR. "Genetic diverseness and population genetic structure in the S American sea king of beasts (Otaria flavescens)" (PDF). Department of Anthropology and Schoolhouse of Biological & Biomedical Sciences, Academy of Durham, U.K.

- ^ a b Gilbert DA, Packer C, Pusey AE, Stephens JC, O'Brien SJ (1991-10-01). "Analytical Dna fingerprinting in lions: parentage, genetic diversity, and kinship". The Journal of Heredity. 82 (5): 378–86. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111107. PMID 1940281.

- ^ Ramel, C (1998). "Biodiversity and intraspecific genetic variation". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 70 (eleven): 2079–2084. CiteSeerXten.i.1.484.8521. doi:10.1351/pac199870112079. S2CID 27867275.

- ^ Kenyon KW (August 1969). "The sea otter in the eastern Pacific Bounding main". Due north American Animate being. 68: ane–352. doi:ten.3996/nafa.68.0001.

- ^ Bodkin JL, Ballachey Be, Cronin MA, Scribner KT (December 1999). "Population Demographics and Genetic Diversity in Remnant and Translocated Populations of Sea Otters". Conservation Biology. 13 (6): 1378–85. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98124.x. S2CID 86833574.

- ^ Wielebnowski, Nadja (1996). "Reassessing the relationship between juvenile mortality and genetic monomorphism in captive cheetahs". Zoo Biology. xv (4): 353–369. doi:x.1002/(SICI)1098-2361(1996)15:4<353::AID-ZOO1>3.0.CO;2-A.

- ^ a b Wright South (1922). "Coefficients of inbreeding and relationship". American Naturalist. 56 (645): 330–338. doi:x.1086/279872. S2CID 83865141.

- ^ Reynolds J, Weir BS, Cockerham CC (November 1983). "Interpretation of the coancestry coefficient: ground for a brusque-term genetic distance". Genetics. 105 (3): 767–79. doi:10.1093/genetics/105.3.767. PMC1202185. PMID 17246175.

- ^ Casas AM, Igartua Eastward, Valles MP, Molina-Cano JL (November 1998). "Genetic diversity of barley cultivars grown in Kingdom of spain, estimated past RFLP, similarity and coancestry coefficients". Establish Convenance. 117 (5): 429–35. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.1998.tb01968.10. hdl:10261/121301.

- ^ Malecot M. Les Mathématiques de l'hérédité. Paris: Masson et Cie. p. 1048.

- ^ How to compute and inbreeding coefficient (the path method), Braque du Bourbonnais.

- ^ Christensen K. "four.5 Calculation of inbreeding and relationship, the tabular method". Genetic adding applets and other programs. Genetics pages.

- ^ García-Cortés LA, Martínez-Ávila JC, Toro MA (2010-05-16). "Fine decomposition of the inbreeding and the coancestry coefficients by using the tabular method". Conservation Genetics. 11 (5): 1945–52. doi:10.1007/s10592-010-0084-x. S2CID 2636127.

- ^ a b Nichols HJ, Cant MA, Hoffman JI, Sanderson JL (December 2014). "Prove for frequent incest in a cooperatively breeding mammal". Biology Letters. x (12): 20140898. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0898. PMC4298196. PMID 25540153.

- ^ "Insect Incest Produces Healthy Offspring". 8 Dec 2011.

- ^ Gardner A, Ross Fifty (August 2011). "The evolution of hermaphroditism by an infectious male-derived cell lineage: an inclusive-fitness analysis" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 178 (two): 191–201. doi:10.1086/660823. hdl:10023/5096. PMID 21750383. S2CID 15361433. Lay summary – Alive Science (July 28, 2011).

- ^ Freeman S, Herran JC (2007). "Aging and other life history characters". Evolutionary Analysis (4th ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. p. 484. ISBN978-0-13-227584-2.

- ^ "Polycystic kidney disease | International Cat Care". icatcare.org . Retrieved 2016-07-08 .

- ^ "Polycystic Kidney Disease". www.vet.cornell.edu . Retrieved 2016-07-08 .

- ^ a b c Tave D (1999). Inbreeding and brood stock management. Food and Agriculture Arrangement of the United nations. p. 50. ISBN978-92-5-104340-0.

- ^ Bosse, Mirte; Megens, Hendrik‐Jan; Derks, Martijn F. 50.; Cara, Ángeles M. R.; Groenen, Martien A. M. (2019). "Deleterious alleles in the context of domestication, inbreeding, and option". Evolutionary Applications. 12 (1): half dozen–17. doi:10.1111/eva.12691. PMC6304688. PMID 30622631.

- ^ G2036 Alternative the Commercial Cow Herd: BIF Fact Sheet, MU Extension Archived 2016-04-xvi at the Wayback Machine. Extension.missouri.edu. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ "Genetic Evaluation Results". Archived from the original on Baronial 27, 2001.

- ^ S1008: Genetic Selection and Crossbreeding to Raise Reproduction and Survival of Dairy Cattle (S-284) Archived 2006-09-10 at the Wayback Auto. Nimss.umd.edu. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ Vogt D, Swartz HA, Massey J (Oct 1993). "Inbreeding: Its Significant, Uses and Effects on Subcontract Animals". MU Extension. Academy of Missouri. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved Apr 30, 2011.

- ^ Top True cat Breeds for 2004. Petplace.com. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ Taft, Robert et al. "Know thy mouse." Science Direct. Vol. 22, No. 12, Dec. 2006, pp. 649-653. Trends in Genetics. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.tig.2006.09.010

- ^ Hamamy H (July 2012). "Consanguineous marriages : Preconception consultation in primary health care settings". Journal of Community Genetics. 3 (3): 185–92. doi:10.1007/s12687-011-0072-y. PMC3419292. PMID 22109912.

- ^ a b c Woodley, Michael A (2009). "Inbreeding depression and IQ in a study of 72 countries". Intelligence. 37 (3): 268–276. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2008.10.007.

- ^ a b Kamin, Leon J (1980). "Inbreeding low and IQ". Psychological Bulletin. 87 (iii): 469–478. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.87.3.469. PMID 7384341.

- ^ a b c d e f Tadmouri GO, Nair P, Obeid T, Al Ali MT, Al Khaja N, Hamamy HA (October 2009). "Consanguinity and reproductive wellness among Arabs". Reproductive Health. vi (1): 17. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-half dozen-17. PMC2765422. PMID 19811666.

- ^ a b Roberts DF (November 1967). "Incest, inbreeding and mental abilities". British Medical Journal. 4 (5575): 336–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.four.5575.336. PMC1748728. PMID 6053617.

- ^ a b Van Den Berghe, Pierre L (2010). "Human inbreeding abstention: Culture in nature". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. half dozen: 91–102. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00014850. S2CID 146133244.

- ^ Speicher MR, Motulsky AG, Antonarakis SE, Bittles AH, eds. (2010). "Consanguinity, Genetic Drift, and Genetic Diseases in Populations with Reduced Numbers of Founders". Vogel and Motulsky'southward man genetics problems and approaches (4th ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 507–528. ISBN978-3-540-37654-five.

- ^ a b Ober C, Hyslop T, Hauck WW (January 1999). "Inbreeding effects on fertility in humans: evidence for reproductive compensation". American Journal of Human Genetics. 64 (1): 225–31. doi:ten.1086/302198. PMC1377721. PMID 9915962.

- ^ Morton NE (Baronial 1978). "Effect of inbreeding on IQ and mental retardation". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the United States of America. 75 (viii): 3906–8. Bibcode:1978PNAS...75.3906M. doi:x.1073/pnas.75.viii.3906. PMC392897. PMID 279005.

- ^ a b Bittles AH, Grant JC, Sullivan SG, Hussain R (2002-01-01). "Does inbreeding lead to decreased human fertility?". Annals of Homo Biology. 29 (2): 111–30. doi:10.1080/03014460110075657. PMID 11874619. S2CID 31317976.

- ^ Ober C, Elias South, Kostyu DD, Hauck WW (January 1992). "Decreased fecundability in Hutterite couples sharing HLA-DR". American Periodical of Human Genetics. 50 (i): half-dozen–14. PMC1682532. PMID 1729895.

- ^ Diamond JM (1987). "Causes of death before nascency". Nature. 329 (6139): 487–8. Bibcode:1987Natur.329..487D. doi:10.1038/329487a0. PMID 3657971. S2CID 4338257.

- ^ Stoltenberg C, Magnus P, Skrondal A, Lie RT (April 1999). "Consanguinity and recurrence adventure of stillbirth and infant death". American Journal of Public Health. 89 (four): 517–23. doi:x.2105/ajph.89.iv.517. PMC1508879. PMID 10191794.

- ^ Khlat Yard (December 1989). "Inbreeding furnishings on fetal growth in Beirut, Lebanese republic". American Periodical of Physical Anthropology. 80 (4): 481–4. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330800407. PMID 2603950.

- ^ Bener A, Dafeeah EE, Samson North (December 2012). "Does consanguinity increase the risk of schizophrenia? Report based on primary wellness care centre visits". Mental Health in Family Medicine. 9 (4): 241–8. PMC3721918. PMID 24294299.

- ^ Karsten-Gerhard Albertsen: The History & Life of the Reidenbach Mennonites (30 Fivers). Morgantown, Pennsylvania 1996, page 443.

- ^ Girotto G, Mezzavilla One thousand, Abdulhadi K, Vuckovic D, Vozzi D, Khalifa Alkowari Thousand, Gasparini P, Badii R (2014-01-01). "Consanguinity and hereditary hearing loss in Qatar". Human Heredity. 77 (1–4): 175–82. doi:10.1159/000360475. PMID 25060281.

- ^ Beeche A (2009). The Gotha: Still a Continental Royal Family unit, Vol. 1. Richmond, Us: Kensington House Books. pp. 1–thirteen. ISBN978-0-9771961-7-three.

- ^ Seawright C. "Women in Ancient Egypt, Women and Police". thekeep.org.

- ^ Male monarch Tut Mysteries Solved: Was Disabled, Malarial, and Inbred

- ^ Bevan ER. "The House of Ptolomey". uchicago.edu.

External links [edit]

- Dale Vogt, Helen A. Swartz and John Massey, 1993. Inbreeding: Its Meaning, Uses and Effects on Subcontract Animals. Academy of Missouri, Extension. Archived 2012-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Consanguineous marriages with global map

- Ingersoll Due east (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inbreeding

Posted by: duncanfachaps00.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Are There Animals That Can Incestually Breed With No Issues"

Post a Comment